October 22, 2025

Birthright Israel Helps the Jewish Family Find Each Other Again

I grew up in Seattle and live in D.C. now. I’m a legal assistant who’s interested in world history and birdwatching. When I was younger, my family wasn’t terribly observant. We'd observe Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah, have a Seder, and light a Chanukiah, but not much more than that. When I was fifteen, my parents got divorced, and my mom started going to a Reform synagogue. She got interested in learning biblical Hebrew and Aramaic, and chanting Torah. She wanted a sense of community, and I did, too.

Over the years I’ve become more observant Jewishly—partly because my family history is very traditional, Hasidic people from Eastern Poland. I inherited my family’s Yizkor book, commemorating Jewish life before the Holocaust. I’ve always wanted to understand the stories, language, and lives of my great-grandparents. I remembered telling my mother, “I don’t want to just celebrate Shavuot at home. I want to see how it’s done at the synagogue.” These days I’m at shul three or four times a week.

I’d always wanted to go to Israel. My Birthright Israel group was small—19 people, which I loved. We really got to know each other, and by the end I felt close with everyone, including the staff. One of my favorite first impressions was right outside Ben-Gurion Airport, seeing two men talking together—one with peyos and a black hat, the other in a military uniform. It struck me that in Israel, people from totally different worlds are still part of the same story.

Two parts of the trip have really stayed with me: our volunteer visit to Schneider Children’s Medical Center and our visit to the Druze community. At the hospital, there was one little girl working on a card for her brother’s birthday. She was concentrating so hard, trying to write “mazel tov” in pencil. We had sticker sheets with letters—one letter per sticker—and I went to find the ones that spelled M-A-Z-E-L T-O-V. I brought them over and asked if she wanted to use them. Her face lit up. She smiled the whole time as she placed the letters, and it felt like a small but real connection, a moment of joy we got to create together right there in the hospital.

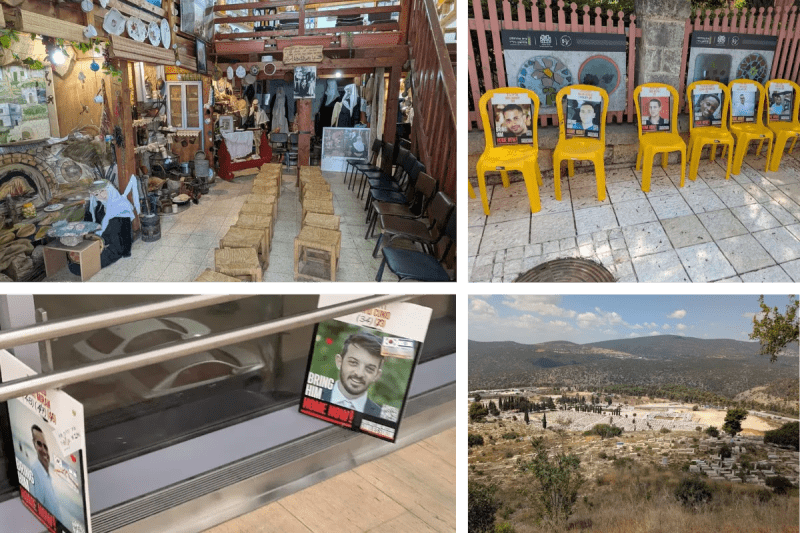

It was about bringing Jewish good wishes into the room in a way a seven-year-old could feel. There were reminders of the heaviness in Israel everywhere—hostage posters, yellow ribbons, empty chairs with names taped on them—and then there I was, helping a kid place shiny letters on a card. It felt like holding both truths at once: grief and joy together.

For the Druze visit, we went to a cultural center in Isfiya, where community members gave a presentation about Druze history and life. They poured us tea and told us about their traditions and beliefs. Afterward they took us on a walking tour. The streets were small and human-scaled, with no tall buildings. Architecturally it felt different from other places we’d been. My mom jokes that many buildings in Israel have “matzah walls,” that yellowish, dappled look, but the houses in this Druze town were more colorful—painted walls, solid structures, hamsas on doors, and blue eyes painted for protection. You could feel the pride and individuality in every home.

At the cultural center, our guide told us about how the Druze originated in Egypt but don’t live there anymore because over centuries they were oppressed and pushed around, treated like nomads. “Now that we have the State of Israel,” she said, “we don’t have to be running anymore.” They can put down permanent roots. I saw that Israel is trying to be a home for everyone, not just the home for the Jews. It felt very hopeful.

Being in Israel after October 7th, we couldn’t miss the reminders. Even walking out of Ben-Gurion, we went down a ramp lined with hostage posters. In little towns there were empty yellow chairs with posters taped on them. It’s a visible, physical reminder that someone here cares enough to set that up and to sweep the leaves off those chairs every day.

We visited Har Herzl. I grew up next to several cemeteries in Seattle, so I thought I was used to them. But there’s a section they added for October 7th victims, and I had never seen that many people mourning on an ordinary Friday morning. The graves were so new. One grave had a little table with a sign: “Read what’s in this book.” It was a photo album of every picture the parents had of their child. It was heartbreaking.

My experience reminded me why I love being part of the Jewish people and made me want to return to Israel as soon as possible. I was literally on the train from the airport looking up flights and researching Birthright Israel Onward. It also made me think about staffing a Birthright Israel trip someday. I love that Birthright helps young Jews see where it all began and where we’re from—and I’d like to help others have that same experience.

If I met the donor who made my trip possible, I’d say thank you, and tell them this program connects people—to Israel, to Jewish community, to family in every sense. On our bus, half the people had cousins or distant Israeli relatives they were eager to meet. For me, it was my ancestors; I used our free time to visit the cemetery where my great-great-grandparents are buried. Birthright Israel helps families get reunited, and in a larger way, helps the greater Jewish family find each other again.

Related Posts

How Birthright Israel Helps Ensure Jewish Continuity

This op-ed by Adela Cojab, Birthright Israel Foundation's Director of Strategic Engagement, was publ...

Birthright Israel Honors Jewish Leader and Philanthropist Jeff Solomon

On December 12, 2024, Birthright Israel Foundation and its friends and supporters gathered at the Ha...

Can Birthright Israel Truly Strengthen the Jewish Future?

You may have heard us say this before: Birthright Israel is strengthening the Jewish future. But Wha...

Elias Saratovsky on How Birthright Israel is Transforming Jewish Life (Podcast)

Birthright Israel Foundation President & CEO Elias Saratovsky joined Jewish Funders Network’s What G...